Intuitive Nature:

Geometric Roots & Organic Foundations

About the Exhibition

This exhibition brings together the work of eight visual artists engaged in abstract, contemporary painting and sculpture. Each artist brings with them a personalized set of tools that reflects their intuitional play on geometric roots and organic reflections. Together, they form an exhibition that is visually stunning, revealing their brilliance and expertise. The artists are selected for their contrasting works as much as their complimentary ones to make the whole of the experience complex yet connected and rooted in like-minded histories.

We are excited to invite back artist and arts writer Shane McAdams whose work has been shown within the Schneider Museum of Art in the 2016 exhibition titled “Exploring Reality” that he co-curated with me. McAdams was tapped to execute the following essay for this exhibition in which he has titled.

-Scott Malbaurn, Executive Director Schneider Museum of Art, Curator

Intuitive Nature: Geometric Roots & Organic Foundations

Essay by Shane McAdams

What art means to the general public and what it means to cultural producers has evolved considerably over the years. A gulf has opened between the two. Like a lot of things, art has gained extra layers of meaning outside its original competencies. If someone in the 1960s had a bumper sticker on their car from an art museum, one couldn’t also presume which brand of bumper it might grace, and it certainly wouldn’t lead anyone to assume for whom they voted. This has changed in the new millennium. Correlations and crosslinks are getting stronger, and it seems that media and markets have done their work to sort us into manageable silos. All the while support for art education and institutions has continued to dwindle. Individual positions cleave more and more along cultural lines in a viscous feedback loop, fueled by new media instruments. Funny that Herbert Marcuse noted in One-Dimensional Man 60 years ago that “The capabilities (intellectual and material) of contemporary society are immeasurably greater than ever before–which means that the scope of society’s domination over the individual is immeasurably greater than ever before.” Clearly, some saw all the division coming and their wild imaginations are finally catching up to our sober realities.

This is a chilling characterization of the contemporary condition, but it gains some context when considering art’s role in society until recently. It would surprise many to know the degree to which Manet’s Olympia shocked Paris when it was included in the Salon of 1863. Not the Parisian “insider” art world, but Parisians en masse. It spilled more ink in the general press than any season of the Kardashians did in gossip rags a century-and-a-half later. One must labor to recall the last time a piece of high culture swelled to that level of prolonged and meaningful discourse. Instead of publicly contested art we now have memes, and replication rather than reception, where value is created privately, not publicly, and whose effect is collective, but not connected. A wardrobe malfunction at a sporting event blows our minds for a week then dissolves into the ether like fireworks. And of course, a meme became president, and we jumped the shark. The Trump-through-pandemic period was an adventure so pathologically surreal that it spread to our surrounding realities, making them feel no more grounded than a film, a song, or a broken piece of gossip, and it’s moved the threshold for what we consider truthful, authentic, and legitimate. Which is why the art form of our time is the NFT, a property that is by nature everywhere and nowhere, something and nothing all at once; rootless and formless and ultimately valueless without consensus.

Over the years, similar critiques have been levied against abstract and conceptual art. Throughout the 20th century, many considered abstraction out of touch with objective and practical reality. It was often seen as a manipulative invention by self-interested leftist radicals without regard for material truths. Recall how Duchamp’s now canonical Nude Descending the Staircase was ridiculed in the press along with the rest of the avant-garde work in the 1913 Armory show. This is most famously reflected in J.F. Griswold’s “Rude” Descending a Staircase in a 1913 New Yorker cartoon. Or more recently a man in a grey flannel suit quizzically regarding what is obviously a Jackson Pollock in the 1962 edition of the Saturday Evening Post. The title of the cover art by Norman Rockwell is Connoisseur, a snarky jab at the pretensions of communing with an abstract work of art.

And still, abstraction has endured as a language. What didn’t kill it made it stronger. Like any language it has laid foundations, weathered assaults, incorporated foreign elements, invented vocabulary, made rules, broken them, thrown them away, and clawed some of them back. Paradoxically, it is in those organic and unplanned challenges that the language of abstraction located its foundations. In the very endurance test of growing up, its roots were allowed to grow downward into the social firmament and provide it with permanence; a permanence that’s easy to take for granted in a world of so much flourish and so little grounding.

The artists in the exhibition Intuitive Nature: Geometric Roots and Organic Foundations at the Schneider Museum of Art reflect this peculiar moment in the course of cultural evolution, a moment where abstraction recognizes its sense of place, purpose, and foundational history. The work in this exhibition is meant to unpack these concerns in a manner that lays out the breadth and sophistication of the language itself. As any linguistic anthropologist would tell you, the structure of all languages is formed along sets of basic binaries. In the case of spoken language, this is you/me; we/they; here/there; none; some; this and that, etc. Visual languages progress along similar lines. With the fluency of their particular tongue, the artists in Intuitive Nature work across multiple perspectives and elemental oppositions to express truths inherent to their medium.

Anna Fidler’s colorful compositions play with one of the most primary, even primordial, of these: the concept of symmetry and asymmetry. Her colorful ‘Energy Portraits’ possess an elegant precision and cosmic universality, even while they feel semi-figural and deeply personal. The type of balance and bilateral mirroring in her work happens to be standard in most living things, and such morphological ordering resonates with humans at a deep level. We conjure menacing creatures in Rorschach tests and sometimes Jesus Christ in pieces of toast. Our species finds patterns, order, and balance everywhere we look…to our pleasure, protection, and peril. And sometimes, in the case of Fidler’s work, we stumble on unexpected associations with art, energy, and how the smallest worlds connect to the cosmically large ones.

Artist Jason Stopa’s paintings live in the margins between familiar and unfamiliar, formal and informal. His off-kilter, semi-animate forms snap or maybe slide and spread, to a provisional underlying grid. The looseness in his compositions leverages the expectations of more rigorous and exacting worlds: Euclidean math, gestalt psychology, and color theory, only to subvert them with intuitive gestural looseness. And only just barely; they live in-between the in-between. Repeated arrays, reflections, and tracers of closed forms are never regular enough to set your instruments or watches. Scalloped fringes? Palsied quatrefoils? His forms narrowly escape such clinical terms. The color, too, is in a major key but ever so slightly off. Not in a minor key, either, but sweet, sweet lilty C-major, sharpened here, flattened there, ever-so-slightly.

The constructions of Mark Sengbusch play off the relationship between two and three-dimensional forms, building complex architecturally motivated sculpture out of repeated interlocking flat shapes. Paired with unusually and decidedly non-architectural color schemes, his work builds basic abstract elements into dimensional arrangements that flirt with things in the visible universe: tables, desk organizers, shelves, kitchen tools. They seduce us with recognition and materiality and quickly melt into pure three-dimensional tessellated abstract form, leaving the world of things you can name behind while retaining a touch of its alluring color and tactility.

Courtney Puckett also makes 3-D work informed by architecture, sculpture, craft and an omnivorous love of materials both soft and hard, two and three-dimensional. Her approach to found objects and repurposed textiles pairs a voracious hunger to produce and conservational mindfulness. Impulses that would seem strange bedfellows if they didn’t produce such strangely unique objects about the idea itself. Puckett’s feral and eccentric constructions inadvertently undermine the precision and predictability of the modern manufacturing machine by upcycling and recovering found objects with a determined vision. This vision retains the residue of machine-made furniture, snap-together appliances, and other container-shipped cargo…but with frayed edges, gnarly surfaces, distortion, and reverb. Nodding to a history of feminist artmaking, Puckett takes the delicate and overlooked and transforms it into robust, assertive art works. Her wirey, twiney sculptures in the exhibition set up brilliant collisions between those historical codes and expressive, improvisational flourishes in a brilliant display of what Roland Barthes identified in photography as the studium and the punctum, with independent material and interdependent significance in constant and generative interplay.

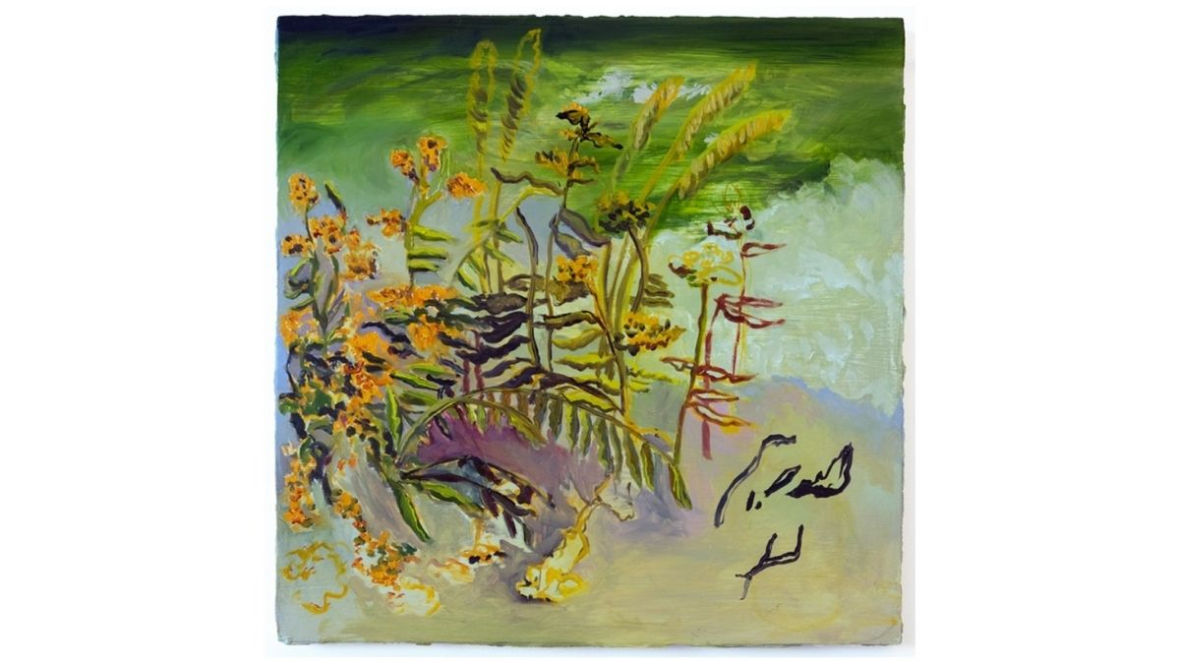

Heather Day’s work feeds off the relationship between chance and control, as well as intuition and logic. Begun in the spirit of action painting and gestural abstraction, Day uses her initial poured and splashed experiments as a material reservoir to irrigate her post-productive compositions. Day’s work inventively rearranges sections of cut canvases into new composite paintings that present the better parts of two independent languages. It’s a painting Esperanto reflective of its post-historical moment, and the results thrive on another powerful and often overlooked force between aleatory and composed beauty. She ends up with the better parts of both in the body of a third.

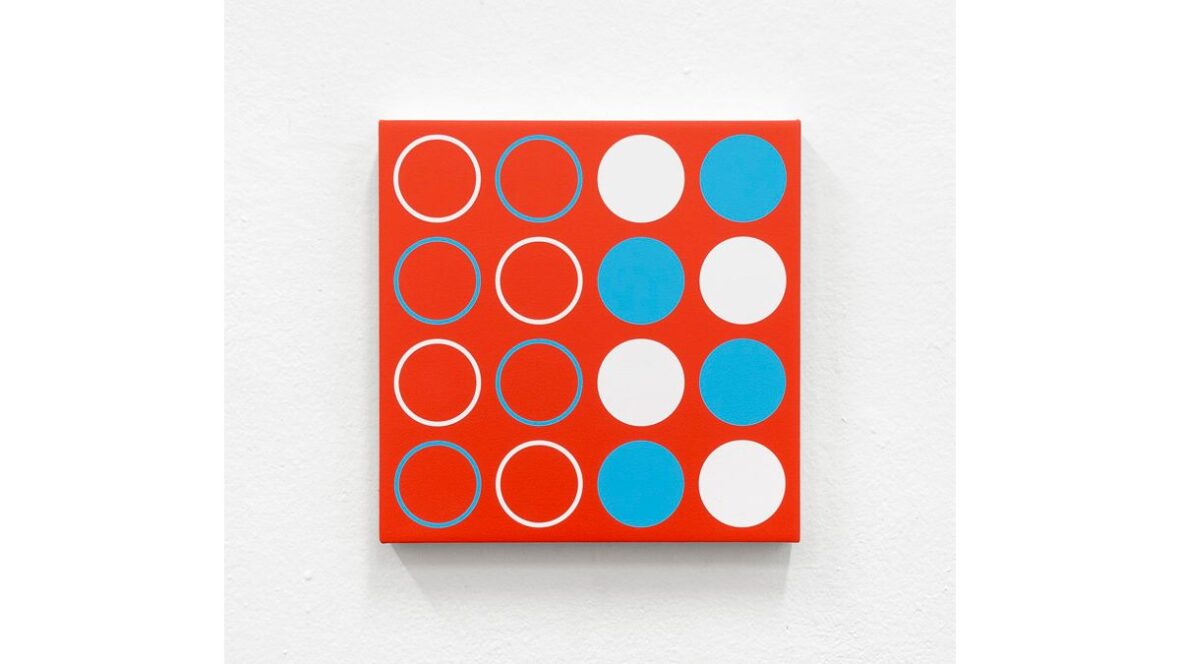

If abstraction is a language, Jan Van Der Ploeg is a grammarian. His visual language is reduced to a set of essential parameters, but he goes wild within that restricted space. Van Der Ploeg’s paintings consequently inhabit another dimension in the non-objective universe, taking a decisive path at the crossroads of contraction and expansion. He took the exit toward contraction and reduction. Or towards the realm, Mies van der Rohe famously consecrated with the phrase “less is more.” His most recent work draws inspiration from record sleeve designs by Josef Albers for Command Records in the late 1950s and early 1960s. Like Albers, Van Der Ploeg economizes his visual repertoire only to turn what might be minimal into maximal compositional inventions.

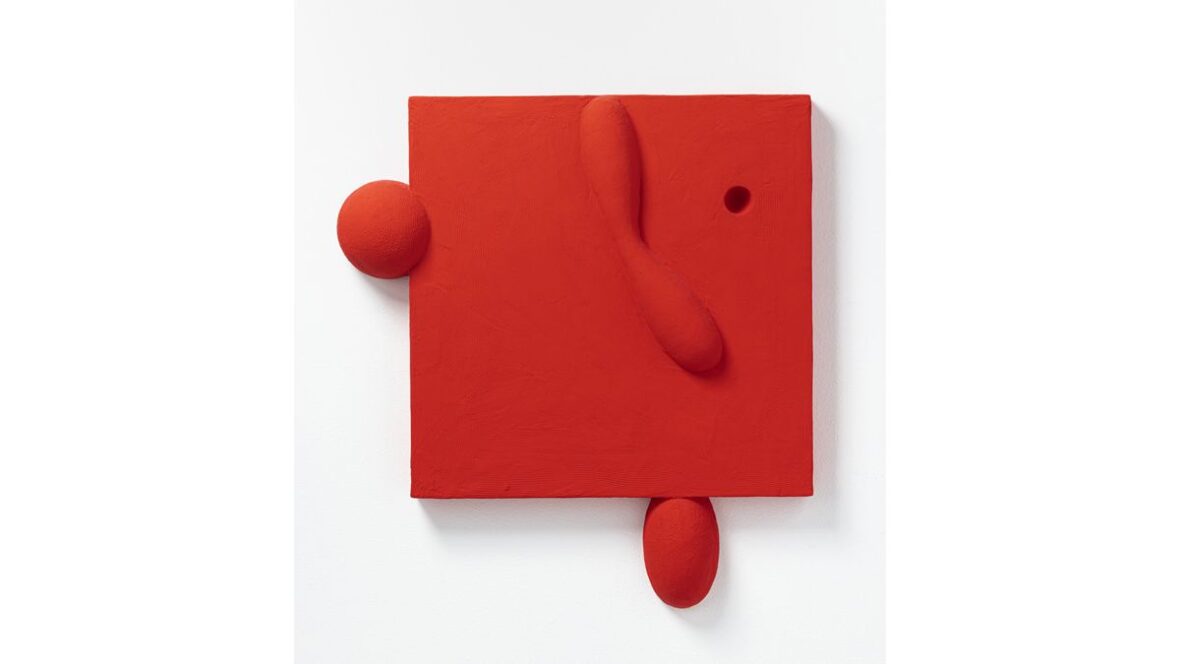

Ivan Carmona pares down the languages of volume and color with a sensibility similar to Van Der Ploeg. But of course, his work scrambles into its own peculiar territory from those initial similarities and his own particular constraints. His mixed media geometric assemblages merge the worlds of monochromatic painting and Brutalist and Futurist sculpture. One thinks of Isamu Noguchi, Louise Nevelson, and Henry Moore, but with the color and personality of a pluralistic and post-modern age. With tools and dimensional imagination not available at the height of modernism. The results of his (re)investigations are as crisp and clean as Puckett’s are gritty and stammering, and as handsomely unified as Van Der Ploeg’s are various. Nevertheless, like each, he tells his version of a complicated story in a resounding and consistent voice.

Andrew Kleindolph’s work embraces the exacting accuracy and regularity of the nano-productive age, working with LEDs, computers, and 3-D printing. It’s an if-you-can’t-beat-them-join-them kind of strategy of co-opting the contemporary world and using it with a creator’s instinct. His work heads bravely into the jungle of massproduction, AI, social media, and endless funhouses of information and imagery. It scans our contemporary funhouse for poetic opportunities to combine themes as disparate as meditation, political data, risk management, and electronic hardware. It’s big, loud, unapologetic, and definitely not your great, great grandfather’s abstraction.

We’re living on the verge of Web 3.0 but it’s easy to forget we’re also firmly inside Abstraction 4.0, and Industrial Revolution 5.0. The first go ‘round of this ongoing civilization transformation saw Luddites throwing wrenches into machinery to sabotage unskilled mass production. Later, others tried to seize the means of production through revolution. And many others then worked on change from the inside trying to reconcile the ancient and the modern and the limits of the human capacity to comprehend any of it. The same historical circumstances hold true for artists who use tools, agency, and language as precisely, powerfully, and persuasively as possible to keep the world around them progressing in good faith. As civilization in 2023 threatens to sink into bad faith, the saboteurs, activists, and truth seekers working in all languages stand out in higher and higher relief. They take on the role of both philosopher and revolutionary. As the saying goes, “when information is cheap, attention becomes expensive.” Rarely has raw and sensitive intuition, deep understanding, and purposeful communication seemed to matter so much. Nor has a non-algorithmic, handmade, language looked so articulate as it does right now. And never has the abstract, like the work we see in Intuitive Nature, seemed more concretely important than it does at this very moment.

Shane McAdams bio:

Shane McAdams is artist, writer, curator, educator, and papa residing in Cedarburg, WI. His artwork has been exhibited at Allegra LaViola Gallery, Marlborough, Chelsea, Elizabeth Leach Gallery in Portland, OR, Scream London, and Artistree in Hong Kong, China, The Haggerty Museum of Art, The Kohler Art Center, as well as other venues. His work has been reviewed in Vogue Magazine, The New York Times, The New York Observer, The Huffington Post, and The Village Voice. He has taught at the Rhode Island School of Design and Marian University in Wisconsin. He is a three-time Creative Capital, Andy Warhol Writer’s Grant finalist, and his writing appeared regularly in the Brooklyn Rail from 2002 to 2012. He has also contributed to The Milwaukee Journal Sentinel and currently writes for the Shepherd Express for which he received the Visual Arts Achievement in Arts Writing from the Wisconsin Academy of Arts and Letters in 2020. In addition to writing and painting, he is also a co-partner in REAL TINSEL, an art space on the Southside of Milwaukee.

Curator

Scott Malbaurn

Artists

Ivan Carmona

Heather Day

Anna Fidler

Andrew Kleindolph

Courtney Puckett

Mark Sengbusch

Jason Stopa

Jan van der Ploeg

Catalog

Available for purchase from the museum’s front desk.

Checklist

Copies available in the Main Gallery