Nathan Oliveira Figure Studies:

Works on Paper, 1989 – 2001

Artist Bio

Born in Oakland, California, Nathan Oliveira earned his bachelor’s and master’s degrees in fine art at the California College of Arts and Crafts in 1952. He also studied during the summer of 1950 with Max Beckmann at Mills College in Oakland. His early works are mainly expressive in form, color, and line. In 1956 Oliveira began teaching at his alma mater and also at the California School of Fine Arts in San Francisco. One year later he received a Louis Comfort Tiffany grant for lithography and began more in-depth work in prints. In 1958 he was awarded a Guggenheim fellowship, which enabled him to travel to Europe. As an artist in residence at the University of Louisville from 1961 to 1962, Oliveira had a solo exhibition at the university’s Krannert Museum. From 1963 to 1964, he was a visiting lecturer at the University of California at Los Angeles, after which he accepted a permanent teaching position at Stanford University. In 1994 he was elected to membership in both the American Academy of Arts and Letters and the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. In 1995 he received an honorary doctorate from the San Francisco Art Institute. Oliveira passed away on November 13, 2010.

Exhibition Essay

A painting style is defined by color deployed in compelling relationships, and it’s determined by the quality of an artist’s meditation on a motif or on a formal idea. It takes shape over a period of time. In drawing, style is literally the action of the stylus, the writing tool, the edged or pointed instrument which, once it begins to make a mark, cracks open an unpredictable process of discovery. A drawing style happens fast, almost instantaneously. The tip of the stylus follows oddly improvised impulses: it responds to the subject, to the artist’s temperament, to formal challenges springing up moment to moment, and to the mood of the hour. The artist writes with the tip of pen, pencil, and brush in order to make intense, spontaneous lyric disclosures. Watercolor especially is responsive to the tremors of the moment. Egon Schiele, an artist Nathan Oliveira admired for a long time, uses his style, that line haunted by nebulous color, to remodel over and over again the body in violent or melancholy argument with itself. Schiele’ s paintings, where he gives up the speed and triggeredness of drawing, are sluggish and blocky poetry.

The elements of Oliveira’s paintings are familiar to us: the human figure flayed upon a stark yet vibrant space; the animal images of kestrel, monkey, and dog; and the stelae and sites, which look like the heavily weathered shrines of some lost mystery religion. The paintings have a stormy solidity, because Oliveira painted out his feeling for the density an ongoing and constantly self-revising improvisation. Instead of painterly ideas, he worked with momentary recognitions that flashed forth in line and wash. It’s as if he needed to drain away the forceful solidities of his paintings and begin working instead with evanescence. In the Imi pictures we’re seeing a mature artist becoming once again a more or less raw student of his own instincts.

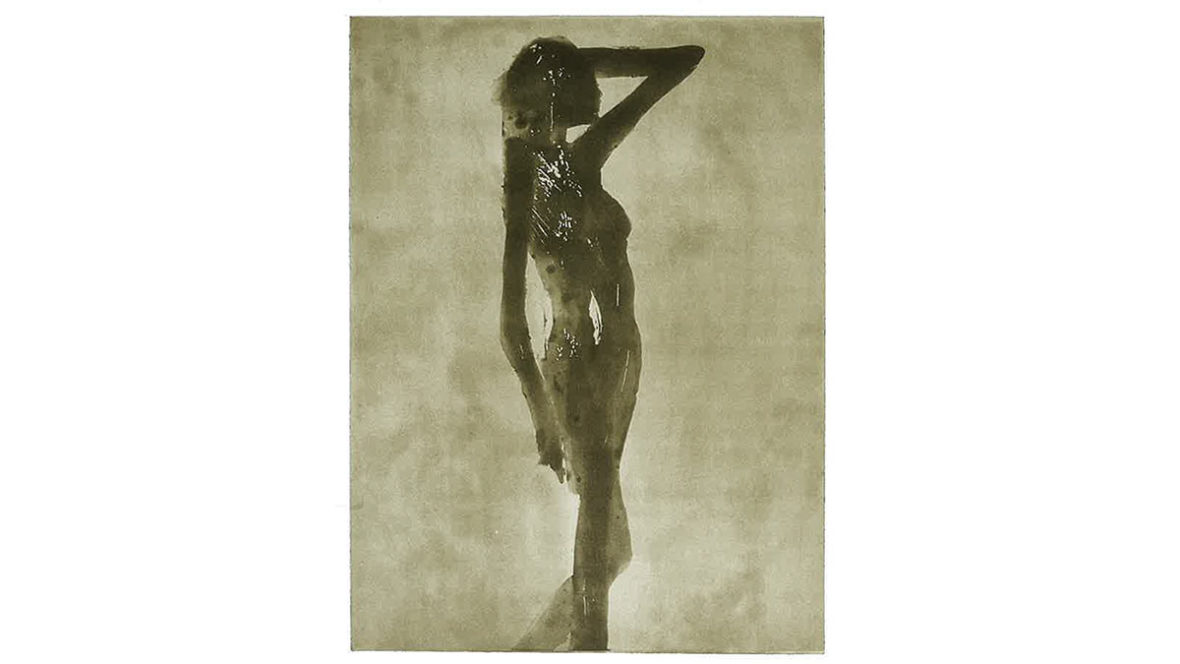

He once said to me in the studio that to him the vertical means life, the horizontal death. From his drawings of the 1960s to his watercolors we see him negotiating all sorts of verticals, seeking to represent different surges and powers of life. There’s a recumbent nude with a teddy bear from 1966 in which the legs of the figure are lifted, as if yearning for the perfect vertical stability of that toy. One of the most powerful drawings from the 1970s is a pen and ink of a nude standing by a stool in which the figure looks incised upon its space, the head lifted with almost priestly dignity. The Imi series is all speed and feeling. Oliveira allowed himself no time to work out formal problems or develop pictorial ideas. The style was from day to day unpredictable, at times virtually abstract, at times classical, almost academic, in its pursuit of likeness. In one drawing Imi is nearly horizontal, her back arched, but far from being an image of lifelessness, it’s an image of flight and action, because her body looks like a wing, indeed like the wings he would paint in the 1990s. From drawing to drawing we watch Oliveira pushing his style, from fisted, tightly scrolled figures to dilated ethereal ones.

The line is an artist’s shape of desire, inquiry, and pursuit. The flesh and shadow washed along the line in Oliveira’s pictures create an image of the body coming into substance, becoming enfleshed, but at the same time perishable and disintegrating. When he pulls the image of Irni from resolution to dissolution, through the mysterious zones of solidity in between, he’s testing the extremities of erasure and realization. This action in itself, I believe, constitutes a major statement, one always subject to revision. There’s a palpable sense that the curvilinear action pulsing in the watercolors is an image of that invisible circulatory stream that runs from model to artist to paper to us, then back around again. It’s like a gift, maybe from the gods, that keeps its value only so long as it circulates among the tribe.

-W. S. Di Piero

Artist

Nathan Oliveira