Across the Continents

Artist Bios

Bernard Buffet

Bernard Buffet is a French painter whose figurative paintings and prints express a sense of anxiety associated with the philosophical movement known as Existentialism. Buffet was born in Paris on July 10, 1928 and studied at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts there between 1944 and 1945. Working under the influence of the French painter, Francis Gruber, he attracted critical attention almost immediately, and in 1948 was the joint winner, together with Bernard Lorjou, of the Prix de la Critique. His commitment to realistic rather than abstract art was demonstrated by his joining the group Homme-Temoin in 1949. Buffet’s career culminated in 1973 with the opening of a museum devoted to his work near Mishima, Japan. The work exhibited at the Schneider Museum was made in 1981 and features the landscapes Buffet visited throughout Japan. His later work includes landscapes, as well as expressive narrative paintings. Buffet’s success lies in his synthesis of “modem” pictorial forms with traditional techniques and subject matter. His popularity was further enhanced by his ability to capture the troubled mood of French society in the post-war era.

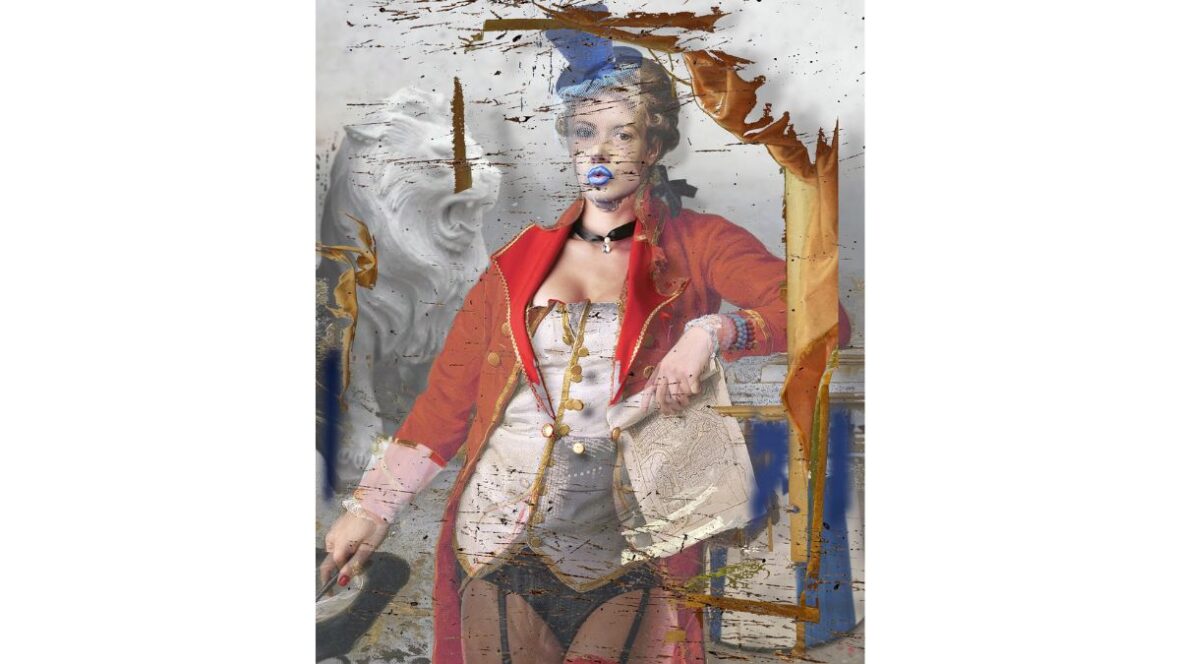

Rafael Canogar

Canogar is a Spanish painter and printmaker born in Toledo, Spain. Educated in Madrid he helped to form the El Paso Group there in 1957. His early work was largely non-objective, but in the early 60’s his style became more figurative, and he began to use a collage method, almost on a scale of sculptural relief. He was a visiting professor of art at Mills College in 1965-66, a guest artist at the Tamarind Lithography Workshop, Los Angeles, in 1969, he then went on to win prizes in competitions in both France and Brazil. In 1972 and 1974 he was Artist-in-residence in Berlin. His figurative work is in the tradition of Francisco Goya and is openly political, where protest, social injustice, wars and violence dominate the images. The suites that were shown in the museum were printed in 1969 and 1972.

David Alfaro Siqueiros

David Siqueiros was a founder, along with Diego Rivera and Jose Clemente Orozco, of modem mural painting in Mexico. He was born in Chihuahua, Mexico, into a cultivated family. His father was a lawyer and his mother the daughter of a renowned poet and politician. As a teenager he was interested in Mexican archeology and folk art. In 1913-14 he studied with Orozco until the Mexican Revolution interrupted his work. From 1914 until 1922 he served on the general staff of the Mexican Army, and began to view painting in relation to the social changes for which he was fighting. Posted in 1920 to the Mexican embassy in Madrid, he came into contact with European cubism, Dadaism, futurism and met Rivera.

On his return in 1922, he was commissioned with Rivera, Orozco and others to paint the murals with forthrightly Communist subjects that characterize the style the world associates with revolutionary Mexico during the 30’s and 40’s. He was often at odds with his own government as an active union organizer and as an officer in the Spanish Republican Army.

By the mid-1930’s Siqueiros was experimenting with various new synthetic materials and industrial techniques, arguing that new vehicles of expression were necessary to express the new (Communist) language of art. One of the techniques was drip painting. In 1935-36 Siqueiros opened a workshop in New York City to demonstrate his new approach, and one member of the workshop was Jackson Pollock, whose own drip style did not emerge until about 1947. Siqueiros did not totally give up the old ways, however. Despite the ringing repudiation of easel painting in the Muralist Manifest, neither Siqueiros nor the other muralist gave it up. And despite Siqueiros’s commitment to develop new methods of painting to suit new ways of political thought, he obviously continued, in some cases at least, to paint with oil on canvas, and we have the evidence that he also continued as a printmaker. The lithographs in the museum’s collection are dated 1968.

In 1940 Siqueiros was one of a group of Stalinists who machine-gunned Trotsky’s bedroom. Trotsky and his wife escaped. Siqueiros was jailed, then released on condition he leave the country. He went to Chile long enough to paint an important mural (since destroyed), then returned to Mexico and received increasingly important commissions. By 1950, Orozco was dead and Rivera was perceived as having lost much of his creative force. Siqueiros was acclaimed as leader of the artistic Left, even winning a prize at the Venice Biennale of that year.

Throughout his life he continued to make murals, easel paintings, prints, and wrote for reviews, gave lectures, traveled the world and continued active membership in the Mexican Communist Party, of which he was executive secretary in 1959. In late 1960 he was charged by the Mexican government with “social dissolution” and imprisoned more for his radical beliefs than for any overt political activities. After his release in 1964, he began an ambitious mural, The March of Humanity in Latin America, a huge undertaking covering 49,000 square feet. It was the first time a building had to be constructed just to house such a work. He received the Lenin Peace Prize in 1967, and was elected the first president of the Mexican Academy of Arts in 1968.

He died in 1974, in Cuemevaca, at age 77. He had spent a lifetime painting his political convictions despite the constant threat of political reprisal. His style was less decorative and colorful than Rivera’s and less expressionistic than Orozco’s. He fused his people’s folklore with the preHispanic Mexican tradition to create his own pictorial language – a realism that remained expressive and did not succumb to the dictates of official Communist “social realism.”

Pre-Columbian Era

When Spanish explorers arrived in what is now Costa Rica at the dawn of the 16th century, they found the region populated by several poorly organized, autonomous tribes. In all, there were probably no more than 20,000 indigenous peoples on 18 September 1502, when Columbus put ashore near current-day Puerto Limon. Although human habitation can be traced back at least 10,000 years, the region had remained a sparsely populated backwater separating the two areas of high civilization: Mesoamerica and the Andes. High mountains and swampy lowlands had impeded the migration of the advanced cultures.

There are few signs of large organized communities, no monumental stone architecture lying half-buried in the luxurious undergrowth or planned ceremonial centers of comparable significance to those elsewhere in the isthmus. The region was a potpourri of distinct cultures. In the east along the Caribbean seaboard and along the southern Pacific shores, the peoples shared distinctly South American cultural traits. These groups–the Caribs on the Caribbean and the Borucas and Chibchas in the southwest–were seminomadic hunters and fishermen who raised yucca, squash, and tubers, chewed coca, and lived in communal village huts surrounded by fortified palisades. The matriarchal Chibchas had a highly developed slave system and were accomplished goldsmiths. They were also responsible for the fascinating, perfectly spherical granite “balls” of unknown purpose found in large numbers at burial sites in the Rio Terraba valley, Cafio Island, and the Golfito region. They had no written language.

The largest of Costa Rica’s archaeological sites is at Guayabo, on the slopes of Turrialba, 56 km east of San Jose, where an ancient city is currently being excavated. Dating from perhaps as early as 1000 B.C. to A.D. 1400, Guayabo is thought to have housed as many as 10,000 inhabitants. The most interesting archaeological finds throughout the nation relate to pottery and metalworking. The art of gold working was practiced throughout Costa Rica for perhaps one thousand years before the Spanish conquest, and in the highlands was in fact more advanced than in the rest of the isthmus.

The tribes here were the Corobicis, who lived in small bands in the highland valleys, and the Nahuatl, who had recently arrived from Mexico at the time that Columbus stepped ashore. In late prehistoric times, trade in pottery from the Nicoya Peninsula brought this area into the Mesoamerican cultural sphere, and a culture developed among the Chorotegas–the most numerous of the region’s indigenous groups–that in many ways resembled the more advanced cultures farther north.

In fact, the Chorotegas had originated in southern Mexico before settling in Nicoya early in the 14th century (their name means “Fleeing People”). They developed towns with central plazas; brought with them an accomplished agricultural system based on beans, corns, squash, and gourds; had a calendar, wrote books on deerskin parchment, and produced highly developed ceramics and stylized jade figures (much of it now in the Jade Museum in San Jose). Like the Mayans and Aztecs, too, the militaristic Chorotegas had slaves and a rigid class hierarchy dominated by high priests and nobles.

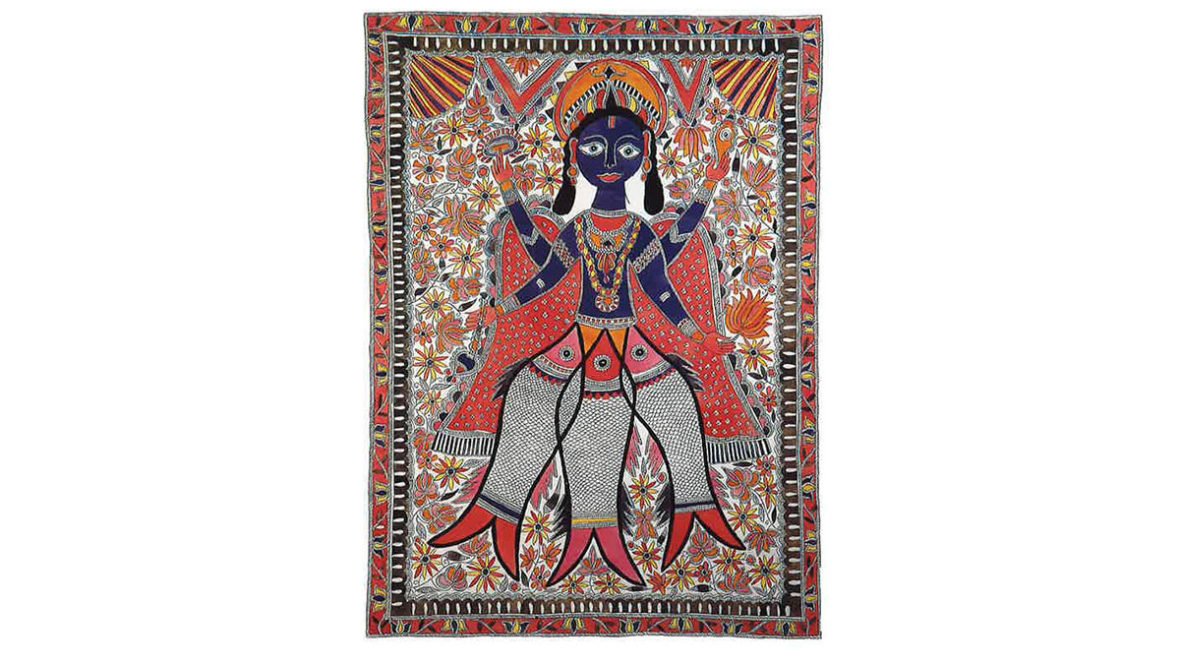

Women Painters of Mithila

Work of eleven women artists (all with the title of “Devi”) of the Mithila area of North-central India. Gift of Betty LaDuke, Emeritus Art Faculty member of Southern Oregon University.

Mithila was an ancient kingdom of India where many of the important religions have originated, including Hinduism and Buddhism among others. Even Gandhi selected Mithila as fertile ground for his message of liberation and economic independence, establishing a spinning and weaving industry there. It is a traditional and rural area where artists and poets have flourished. For almost three thousand years the women – only the women – of Mithila have been making devotional paintings of the gods and goddesses of the Hindu pantheon. A matriarchal society, girls start at an early age to learn the traditional art forms from their mothers. The painting is a religious act and done in conjunction with meditation. If well executed, the god invoked is supposed to inhabit the painting. One type of design–the “kohbar,” based on sexual imagery–serves as the girl’s proposal to a young man of her choice and is used to wrap gifts which are part of the marriage ceremony. Another type, the “aripana,” or what the Buddhists call the mandala, is circular in design and meant to represent the universe and home of the gods.

Some of the works are intricate in line but use little color; others are brilliant in color but simple in form. Still others are highly complex in both design and color. Although all are based on the Hindu legends and use many of the same gods and symbols, no two seem to be alike. Krishna is quite often identifiable by his flute. Kali–such as the decapitated Kali with blood gushing from her neck into her mouth, or many-headed dancing on her prostrate spouse–is usually fierce and frightening. Vishnu appears in many forms, from fish to human. The snake goddess is in many paintings, and tigers, elephants, monkeys, rats, all appear as manifestations of the gods.

This group of paintings was purchased by Betty LaDuke during the 10-year period she spent researching women artists around the world. Her research culminated in the writing of the book Women Artists: Multi-Cultural Visions which would serve as a good resource guide if you are interested in more detail on the artists and this subject matter.

Exhibition Statement

The Schneider Museum of Art presented the work of several international artists featured from the museum’s permanent collection. The fall exhibition included the work of David Siqueiros (Mexico), Rafael Canogar (Spanish), Bernard Buffet (French), Women Painters of Mithila (India), Pre-Columbian artifacts from Costa Rica, and two masks and a shield from New Guinea. The work of Siqueiros and Canogar were greatly influenced by the political climate in their countries and that is reflected in the content of their artwork. The Pre-Columbian, Mithilan, and New Guinea work provide a contrast and history to the more contemporary work of the other artists.

Artists

Bernard Buffet

Rafael Canogar

David Alfaro Siqueiros

Pre-Columbian Pieces from Costa Rica

Pre-Columbian Era

Women Painters of Mithila