Apocalypse

Exhibition Overview

An exhibition co-curated by Richard Herskowitz (Executive Director of the Ashland Independent Film Festival) and Scott Malbaurn (Director of the Schneider Museum of Art) featuring media related art by Matthew Picton, Bruce Bayard, Stephanie Syjuco, Morehshin Allahyari and *Deborah Oropallo.

*Deborah Oropallo’s work was on view at the Hanson Howard Gallery April 5th – 23rd.

Located at:

89 Oak St.

Ashland, OR 97520

Tuesday – Saturday 11am – 5pm

Contact: 541-488-2562

Exhibition Essay

Apocalypse When?

By Richard Herskowitz

Southern Oregon in the summer of 2018 was, for nearly eight weeks, shrouded in wildfire smoke. Many of its inhabitants roamed the streets wearing N95 respirator masks, actors in an apocalyptic movie that was not a movie.

For many, the rise in fires and floods and other natural disasters portends a threat to human survival. Yet this is not an apocalypse delivered by god’s judgment. It is one that may arise from our societies’ inability to slow down the accumulation of wealth and exploitation of nature.

According to artist Matthew Picton, whose work is featured in the Apocalypse exhibition:

The predicaments of today have some of their origins underpinned by the arrival of the seemingly insatiable appetites of the 19th century upon the shores of the new world….The Spanish Conquistadores set in motion a pattern of theft, deceit and violence that could be seen as acting as a template for the future extraction of riches, the notion that vast wealth was for the taking by whatever means. [i]

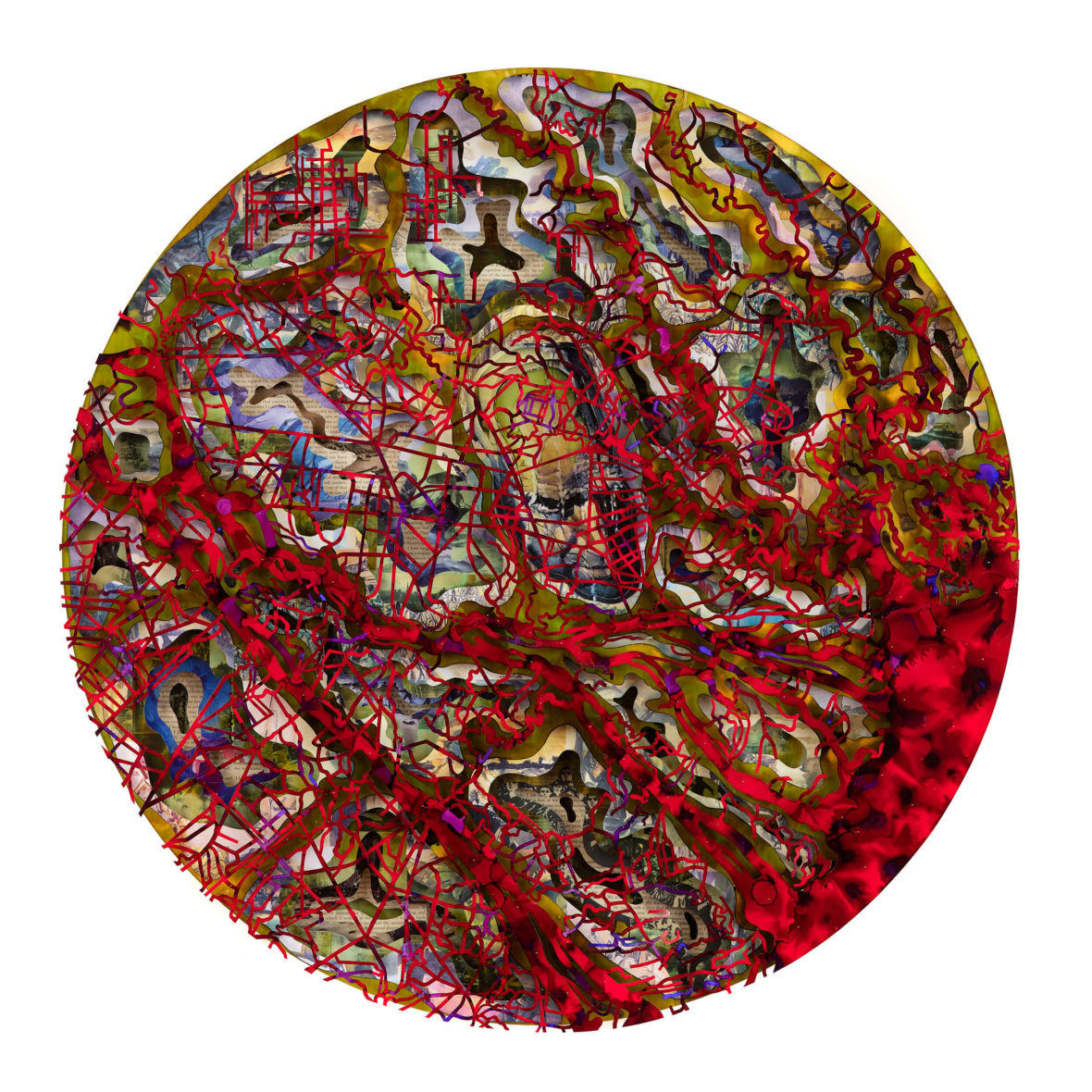

Picton’s artwork on display at the Schneider Museum of Art are in the medium he has mastered– layers of paper cut to form three-dimensional cartographic sculptures. They map territories, including the Congo, Amazon, and Mekong river systems, that have been subjected to human exploitation and conquest. The layers allow Picton to expand standard cartography and weave in paintings, posters, cartoons, and literary texts that reveal histories of domination and resistance embedded in the landscape.

The most prominent source of images cut up and woven into Picton’s sculptures are movie posters and stills, whose films illuminate their terrains. Two particular movies are featured in three of his works in this exhibition, Apocalypse Now and Aguirre the Wrath of God. The sculptures titled Apocalypse Now #1 and The Mekong River, Apocalypse Now #2map the Mekong River that Willard (Martin Sheen) and his team traversed on their hunt for Colonel Kurtz (Marlon Brando). El Dorado portrays the Amazon River that Klaus Kinski as the 16thcentury conquistador Aguirre traveled on his hunt for riches.[1]Apocalypse Now, is celebrating its fortieth anniversary, and Aguirre the Wrath of Godare centerpieces of the 2019 Ashland Independent Film Festival, and I consider them masterpieces. The films depict western warriors; they expose the destructive nature of western colonialism, from the 16thcentury conquistadors of the new world through the 20thcentury war in Vietnam and beyond.

The artists in the Apocalypse exhibition open the colonial prison doors and release the repressed voices of the colonized. Picton incorporates artwork by Viet Cong artists in his second Apocalypse Now sculpture. Stephanie Syjuco was born in the Philippines, the country where Coppola filmed, employing her homeland as Vietnam’s “body double.” In Syjuco’s Body Double (Platoon/Apocalypse Now/Hamburger Hill), she takes her native country back: “I used the three Hollywood films and edited out all the scenes of battle and dialogue, cropping the frame to focus in on the peripheral landscapes (if any) in an attempt to ‘search for the Philippines.’”[ii]In her video Ornament & Crime, she takes Le Corbusier’s iconic French modernist building Villa Savoye and digitally overlays it with the ethnic textile patterns of former French colonies Vietnam and Algeria. She claims this as her own version of “dazzle camouflage,” a technique used by first world militaries to disguise their warcraft.[iii]

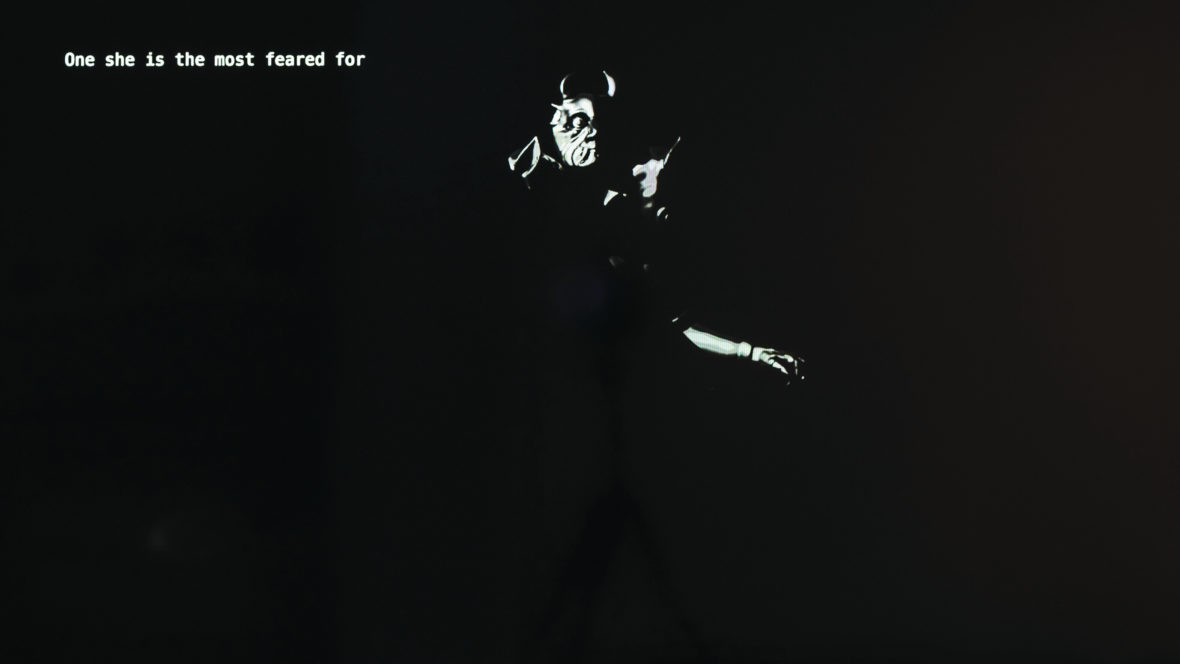

Morehsin Allahyari was born in Iran and, like Syjuco, moved to the United States. She has been creating a body of work on “Digital Colonialism,” using 3D scanners and printers to turn Middle Eastern goddesses and djinns into transformational activists for the present. In She Who Sees the Unknown: Huma, Allahyari takes the djinn Huma, known for “bringing heat,” and applies her to the discussion of global warming.[iv] She sees this discussion as being Western-centric, citing Erik Swyngedouw’s essay, “Apocalypse Now! Fear and Doomsday Pleasures”:

While the elites fear both economic and ecological collapse, the consequences and implications are highly uneven. The elite’s fears are indeed only matched by the actually existing socio-ecological and economic catastrophes many already live in. The apocalypse is combined and uneven. And it is within this reality that political choices have to be made and sides taken.[v]

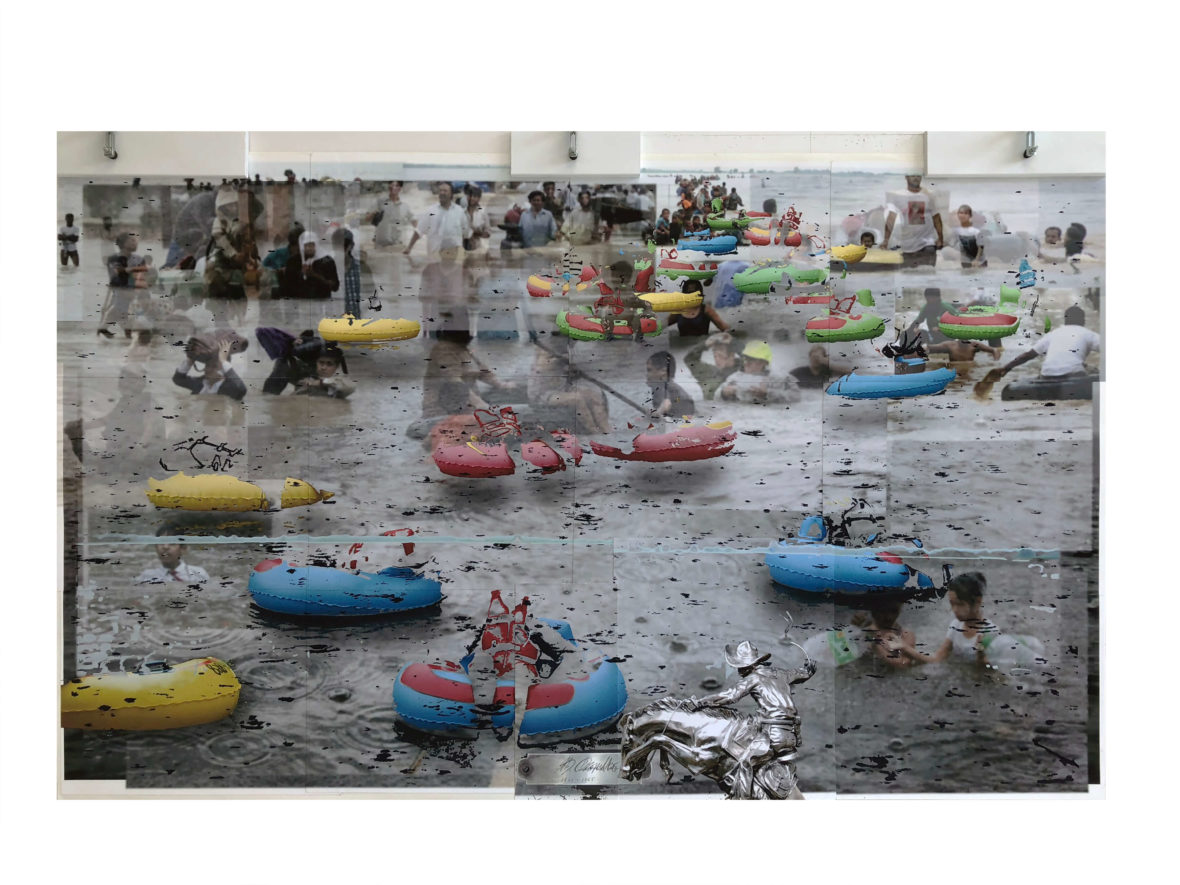

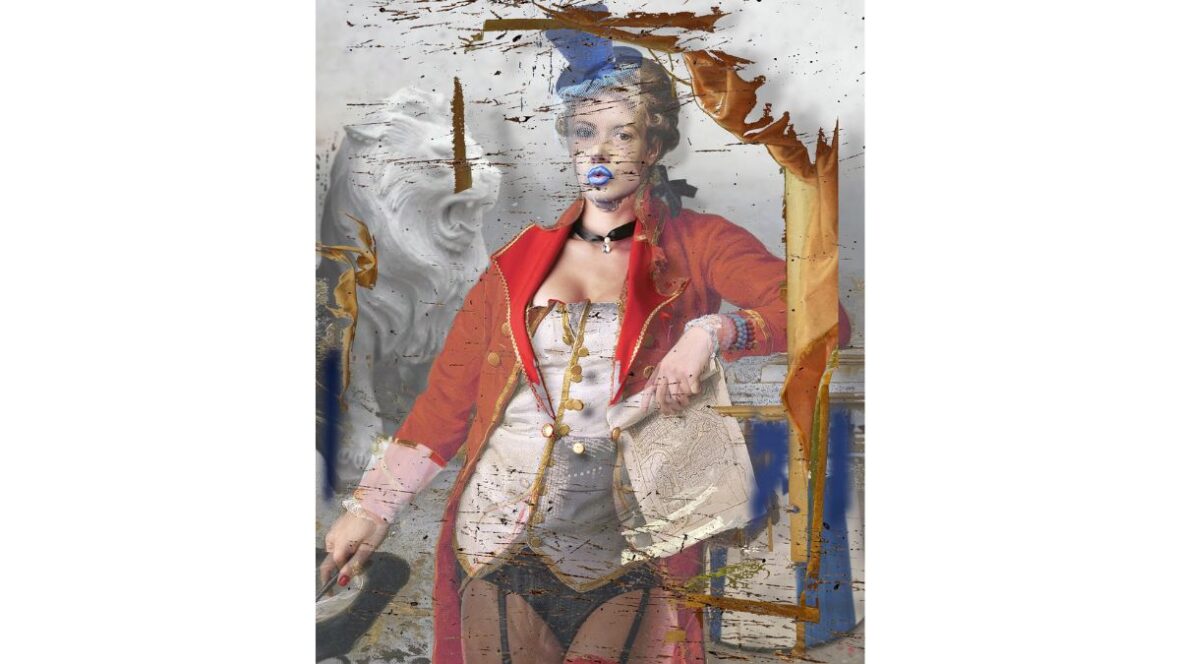

The artist Deborah Oropallo also takes on the calamity of climate change and our inability to think about it clearly and effectively. Her series of videos and photocollages on view at the Hanson Howard Gallery in Ashland, OR, our exhibition’s satellite site, is called Dark Landscapes for a White House, named for the venue where she would rather have the works seen. “I want the president to see the effects of his inaction,” she explains.[vi]Oropallo meticulously layers news images of global disasters, including the wildfires that traumatized the Bay Area where she lives. While inundation by news imagery inures us to disasters, Oropallo slows down and reveals patterns in the onslaught, giving viewers the opportunity to not stare blankly, but reflect actively.

Working with video collage and “Chaos Theory”; a branch of mathematics focusing on the behavior of dynamical systems that are highly sensitive to initial conditions, Bruce Bayard writes code commonly associated with web pages to create complex, ever changing and never repeating collages of projected images. Understanding Bayard’s Triptychs 2019-04, viewers must understand that chaos has several applications in real world environments such as weather patterns, ecosystems, water flows, anatomical functions, organizationsas well as military analytical decision making. The essence of this understanding is that while chaos appears random, chaos properly understood is a deterministic series found in very simple forms. In the context of Apocalypse, Bayard’s systemic noise delivers a psychological punch touching on many of the shared themes within the exhibition.

Discussing his conception of Apocalypse Now in 1979, director Francis Ford Coppola acknowledged, “Aguirre, with its incredible imagery, was a very strong influence.”[vii]The two films’ commonalities go deeper. In both, a white colonial explorer (Kurtz, Aguirre), traveling deep in the jungle, bent on conquest, armored with western cultural trappings, and seeking godlike status among the natives, is ultimately driven mad. [2]The madness that befalls the characters, the landscape, and the film (the wild montage at the end of Apocalypse Now, the invasion of the monkeys in Aguirre the Wrath of God) in one sense appears to be the arrival of Armageddon. But it is not the end of the world, the directors Coppola and Herzog imply. It is simply the murderous and self-destructive end of the western colonial project, which appears to its beneficiaries to be the Apocalypse. In Fredric Jameson’s words, “It is easier to imagine the end of the world than to imagine the end of capitalism.” [viii]

footnotes:

[1]Picton wrote me in an emall, “In a sense Klaus Kinski as Aguirre was the personification of The Apocalypse, Aguirre himself representing a destroying Angel.” Today, President Jair Bolsonaro, the “Tropical Trump,” is the resurrection of Aguirre, threatening the Amazonian rainforest, and therefore the world, with the lifting of environmental protections. The danger is spelled out in Philip Fearnside’s article, “Apocalypse Now for Amazonia: Devastating Promises by Brazil’s President-Elect.”

[2]Variations on this narrative play out in other movies that fascinate me, including Herzog’s Fitzcarraldo, Dennis Hopper’s The Last Movie, and Alex Cox’s Walker. Interestingly, all these white male conqueror films have in common the fact that their crews and productions grew notoriously as wild and nearly out of control as their subjects. Many inspired “making of” films, arguably as good or better than the films they’re about, including Burden of Dreams, The American Dreamer, and, featured in AIFF 2019, Eleanor Coppola’s great Hearts of Darkness: A Filmmaker’s Apocalypse.

[i]Matthew Picton, http://matthewpicton.com/eldorado-2018/

[ii]Stephanie Syjuco, https://www.stephaniesyjuco.com/projects/body-double-platoon

[iii]Stephanie Syjuco, https://www.stephaniesyjuco.com/projects/dazzle-camouflage-propositions-effed-up-eye-hurt

[iv]Morehsin Allahuyari, http://www.morehshin.com/she-who-sees-the-unknown/

[v]Erik Swyngedouw (2013) Apocalypse Now! Fear and Doomsday Pleasures, Capitalism Nature Socialism, 24:1, 9-18.

[vi]Sam Whiting, “Deborah Oropallo’s mesmerizing videos of environmental calamity at Catharine Clark Gallery,” San Francisco Chronicle, May 30, 2018, https://www.sfchronicle.com/art/article/Deborah-Oropallo-s-mesmerizing-videos-of-12937884.php.

[vii]Peary, Gerald. “Francis Ford Coppola, Interview with Gerald Peary”. GeraldPeary.com.

[viii]Fredric James, “Future City,” New Left Review 21, May-June 2003, https://newleftreview.org/II/21/fredric-jameson-future-city.

Curators

Richard Herskowitz

Scott Malbaurn

Featured Artists

Matthew Picton

Stephanie Syjuco

Morehshin Allahyari

Bruce Bayard

*Deborah Oropallo